by Claire Kelly

I grew up in a 1970’s semi with a garden so regimented my mother planted the snapdragons and montbretia using a set square and a spirit level – really! It was a classic example of an aspirational garden – a testament to the human desire to whip nature into shape and show her who’s boss. I therefore grew up with a sense of gardening as an act of defiance against the chaos of nature in her true form.

How things have changed! Even the more recent re-framing of the common usage names for those plants now reflect their true form. Derived from the Greek words “anti,” meaning like, and “rhin,” meaning nose, antirrhinum is a fitting description of this snout-shaped flower of the snapdragon. Likewise, Crocosmia (once known as montbretia) from the Greek words krokos, meaning “saffron”, and osme, meaning “odor”, so-called because the dried leaves of these plants, when immersed in hot water, emit a strong smell similar to saffron.

I may be a romantic, but these names are not only more reflective of the appearance of these plants, but they are also much more enjoyable from a sensory point of view. They roll off the tongue more smoothly, and invite you to repeat them and really soak in the sound.

When I began creating my own garden in my mid-20’s – a signifier of ‘growing up’ and being responsible for something other than my own entertainment – I found myself automatically planting in neat rows with a sense of frustration when the garden deviated from my vision of order. It flopped, it spread, parts of it died, others grew too vigorously. In sum, I had ‘failed’ before I had really begun. The garden had become a challenge. Almost setting myself up to fail, I bought seeds for the most difficult-to-grow plants or the most I’ll-suited to my garden’s soil and situation. I would then rail at my misfortune and curse the natural elements when they didn’t thrive.

I now recognise that what had been intended as ‘me time’ – a reconnecting with the earth and a chance to be fully present in what I was doing – had become another opportunity to shift into ‘doing or striving mode’. I had been gardening as I had been living the rest of my life: an autopilot, constantly thinking ahead to the next thing that needed doing, worrying about what might happen if it didn’t result in perfection, or ruminating about what hadn’t gone well previously. Meanwhile, I was trying to achieve a sense of control in my garden in what otherwise felt like a chaotic and unpredictable world.

Around the same time, work-related stress and anxiety had left me feeling exhausted. I had no reserves left other than those needed to just get through my days. After an autumn and winter of leaving the garden to fend for itself, I walked out into the fresh air one day in May and noticed something wonderful. While there were inevitable weeds poking their heads through the soil (including the universally reviled ground elder), there were swathes of sky-blue forget-me-nots, and a number of plants I realised had been lovingly planted by the previous owners of the house: red peonies, hardy geraniums in pinks and purples, and the pendant flowers of cerinthe or ‘honeywort’. There was no order or ground-plan to where they appeared, but instead they jostled for position and found a happy place to sit next to their neighbour. Even the colour scheme melded together in a strange kind of harmony.

I began to change how I approached the whole thing. I was less caught up with spacing distances between plants, or a rigid colour scheme, and instead began to notice the shape of their leaves, the smell of the soil, and the alchemy involved in planting a seed and simply watching it grow.

When some didn’t flourish or even germinate, I just let it go, and focused on those that had. I even managed to change my relationship with ground elder, giving it its own enclosed patch of the garden in which to do its own thing, and adding its young leaves to salads and its beautiful lacy flowers to displays.

It doesn’t matter how much or little experience you have of gardening; from an evolutionary perspective, working the soil is ingrained in our DNA. Sowing and tending plants takes us out of ourselves, forging a connection with the world around us. The physical nature of gardening supports physical health including cardiovasular and muscle development, as well as the pleasant effects of endorphins released when we dig, prune or weed.

The benefits of gardening for mental health has also been evidenced through many research projects, including ‘Ecominds’, where 12,071 people living with mental health problems were involved in green/gardening activities to improve confidence, self-esteem, and their physical and mental health. There was a statistically significant rise across all parameters.

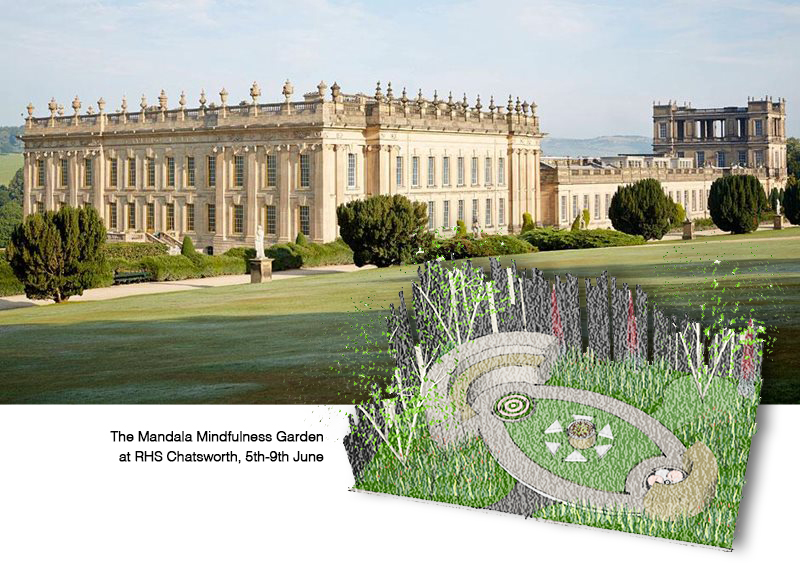

The inherently mindful qualities of gardening are now well-documented. Indeed, the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) has published its own book: ‘RHS Gardening for Mindfulness’, and this year’s RHS show at Chatsworth features not one, but five gardens with a mindfulness theme.

We are therefore particularly excited to be working in collaboration with Heldquin Design Partnership to present The Mandala Mindfulness Garden at RHS Chatsworth June 5th – 9th, 2019. This beautiful garden is designed to work within the limited space of a primary school, and we’ll be there as part of our Million Minds Matter campaign, offering examples of how the garden can be used by schools, and the benefits of introducing young people to gardening more generally.