Did you know that if you Google mindfulness training, the search gives rise to 399,000,000 results? At least, that was today’s count.

Did you know that if you Google mindfulness training, the search gives rise to 399,000,000 results? At least, that was today’s count.

It therefore comes as no surprise that, when applying to take part in MiSP’s teacher training courses, there’s a certain amount of confusion when trying to identify what previous mindfulness training and experience applicants might have had.

Why the explosion in interest?

Why has there been such a rapid growth in the popularity of mindfulness-based training? Certainly, the surge in research evidence relating to the potential benefits of mindfulness programmes has had something to do with it.

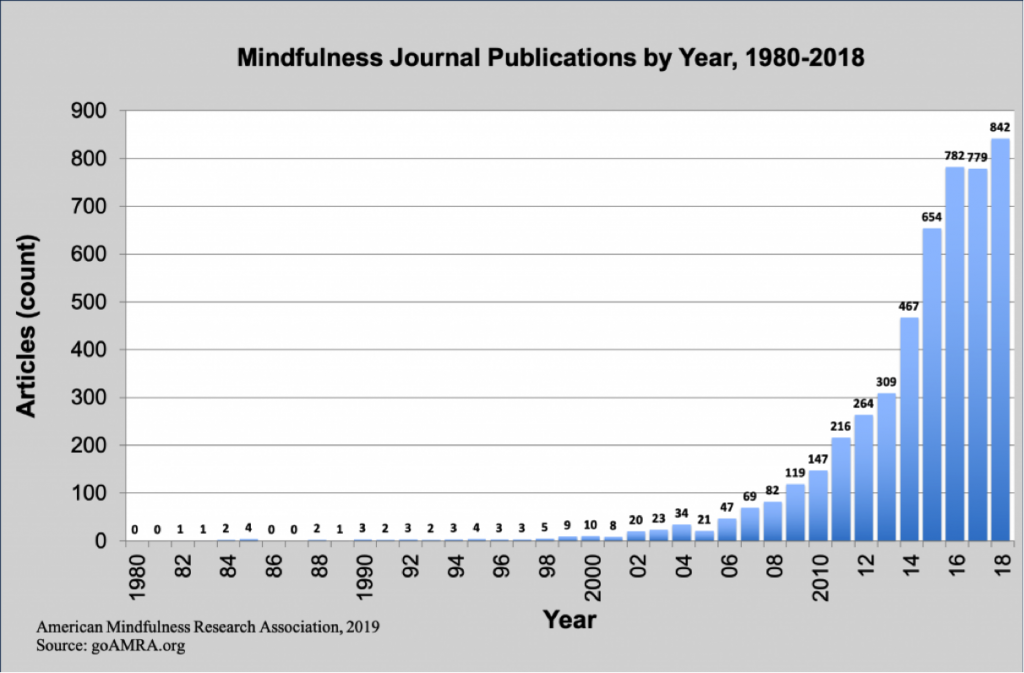

There has been exponential growth in the number of academic research-based publications about mindfulness over the past 35 or so years. During the early 1980s, while Jon Kabat Zinn was still establishing his Stress Reduction Clinic, and offering the secular 8-week Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) courses at the University of Massachusetts Medical Centre, there was next to no mindfulness-related research taking place. By 1993, however, the clinic had treated over 10,000 people with a broad range of conditions, including chronic pain1, anxiety disorders, heart disease, gastrointestinal problems and even AIDS. While the MBSR course had not cured them of their illnesses, evidence showed that most experienced long-lasting physical and psychological symptoms reduction. The mid-1990s also marked the point at which Zindel Segal, John Tesdale and Mark Williams had begun to explore an adapted version of MBSR with the specific intention to help reduce relapse for people with recurrent depression. This went on to become the world-renowned Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy programme (MBCT).

From here on in, research interest in the clinical and non-clinical applications of mindfulness surged, with most recent reports of research-based publications on mindfulness topping 147 in 2010, and 8422 in number through 2018 (see below).

Clearly, this relatively swift growth in academic engagement has helped to feed a broader interest in mindfulness. Likewise, its applications to a range of illnesses and other very human issues must also have something to do with the (misled) tendency to see mindfulness as offering a ‘universal panacea’.

When coupled with a growing sense of the scale of mental illness amongst both young people and adults, it is not surprising to see mindfulness ‘out there’ in the general zeitgeist.

It’s like the Wild West out there

Back to Google and the 399,000,000 results. Here we see a mind-bending range of courses in terms of structure, content and format. They range from 3-year intensive, retreat-based programmes through to ‘How to Become a Mindfulness Teacher in One Day (with no previous mindfulness experience needed)’!

While some of these offerings may be well-intentioned, many have not been researched at all. Some have been constructed based on instinct or simply stuck on to existing therapeutic or wellbeing-based programmes to fit in with time available.

Finally, there is a sub-set of offerings that are of greater concern. Quick-fix courses that promise outcomes for which there is no evidence, usually created by people with no or little formal training in teaching mindfulness, and with a key intention to add it to their collection of training offerings to make money. Some days, this increase in number of such courses feels very akin to the prospectors arriving in California as part of the great Gold Rush of the late 19th Century, heading west in their thousands in search of wealth.

So what does ‘good’ mindfulness training look like?

Before I continue, I want to clearly that many mindfulness courses currently being offered within the UK and beyond are truly excellent. Based on models that have proven effective in supporting both the mental and physical wellbeing of those who follow them, and well researched in their own right, there is now a wealth of courses available to the public, taught by highly competent and extensively trained adult mindfulness teachers. You will find many of them listed on the ‘go-to’ website of the British Association of Mindfulness-Based Approaches (BAMBA), whose main aim is to, ‘…support and develop good practice and integrity in the delivery of Mindfulness-based approaches, in order to contribute to the wider ambition of making MBAs, offered by well-trained teachers, available to all who can benefit from them.’

Here you will also find the Good Practice Guidelines which outline what constitute well-designed and researched training courses for a range of participant groups, and thorough mindfulness-based teacher training.

Understanding what mindfulness is and isn’t

On reflection, it’s not surprising that there is some confusion about what mindfulness actually is and isn’t. On a superficial level, mindfulness looks like a piece of cake. All you have to do is sit in silence, observing your breath. Then you have to eat a raisin unfathomably slowly. How hard can it be?

Of course, the same could be said about swimming (just moving your limbs while the body lies in water), playing the piano (placing your fingers off and on black and white keys), or writing a book (moving a pen up and down on some paper). It’s the apparent simplicity of what’s involved that confuses people. It is the experiential learning involved in mindfulness that helps to clarify what it actually is and isn’t.

Common misconceptions about mindfulness include:

- It’s a breathing exercise

- It’s basically the same thing as yoga

- It’s about emptying your mind

- It’s about taking your mind somewhere else, like a beautiful beach or a mountain top

- It’s new age, hippy stuff

- It’s something anyone can teach

What mindfulness actually involves

(when taught by a well-trained teacher of a recognised and well-researched programme):

- Practising the skill of deliberately paying attention to what is happening in the mind and body, including those which may no longer be helpful.

- Learning the difference between reacting and responding, and how to create the space to make a choice between the two possible.

- A chance to learn how to respond more helpfully to the ‘stresses and strains’ of daily living.

- A way of tuning in to what is positive and helpful in life.

- Recognising the signs of stress and other difficulty before it has the chance to overwhelm you.

- An opportunity to practise care and compassion for oneself and for others.

How do I know whether a course is well-regarded and researched?

Generally speaking, the most thoroughly researched adult mindfulness courses take an 8-week format, following in the footsteps of Jon Kabat-Zinn’s MBSR course (see above). They may vary in terms of their title, but will generally involve weekly sessions of between 90 minutes and 2 hours.

As a general guide, have a look at Appendix 1 List of Courses on the BAMBA website. This is by no means an exhaustive list, so do get in contact if you need to check whether a course you are thinking of doing fits into this category.

Having said all this, there are some situations in which the 8-week format may not be possible, especially in cases where participants are spread across large geographical areas, or only have limited time frames in which to work. In these cases, more condensed formats can work, e.g. 4 lots of 2 sessions. If in any doubt about which of these alternative formats might be recognised/acceptable, just get in touch.

What does a well-trained mindfulness teacher look like?

Again, a good place to look is the BAMBA website, where the key factors are laid out, including the completion of an in-depth, rigorous mindfulness-based teacher training programme or supervised pathway over a minimum duration of 12 months.

A key question to ask your potential mindfulness teacher should therefore include:

‘What formal adult mindfulness teacher training did you follow, over what period, where and with whom?’

Things to watch out for:

1. Do they have their own mindfulness practice? A mindfulness teacher’s own well-established personal practice is crucial in terms of their own experiential understanding of the programme they are teaching, as well as their ability to support you over the weeks of training. This needs to be experience of mindfulness specifically. In other words……

‘Just as in rock-climbing, those who are learning need to feel that the instructor has both the skill and experience to deal with the [any]… difficult situations that arise. In the same way, mindfulness training involves the instructor participating alongside the [participant], not giving instructions, as it were, from the bottom of the rock face.’3

2. How long have they trained for? If their training has lasted less than a year, what form did their training take, and is it recognised by BAMBA or MiSP?

If their training experience was part of a broader, non-mindfulness course, e.g. part of a post-graduate qualification/degree in counselling, psychotherapy or similar, it is unlikely to be a recognised adult mindfulness training unless it is affiliated with a recognised mindfulness teacher training organisation.

If they already work in a clinical or other mental health context, this still doesn’t mean that they will automatically have the training, skills or experience to teach an adult mindfulness course.

3. Yoga – Just as training to teach mindfulness doesn’t then equip you to teach yoga, having trained to be a yoga teacher does not then qualify someone to teach mindfulness. While there is some cross-over in terms of practices and intentions, especially in the mindful movement sessions in mindfulness 8-week courses, the essential structure of an 8-week mindfulness course involves very specific skills and understanding.

4. Online Mindfulness Courses – As a means of increasing accessibility to mindfulness training, the number of mindfulness courses available online is increasing rapidly. Again, many are excellent, and provide opportunities for those who otherwise might be able to access training to follow an 8-week course. However, those which are based on pre-recorded teaching, with no live discussion or ‘enquiry’ are missing a key piece of learning. Mindfulness is not so much about just doing the practice, but what is learned from it, and how it fits into a broader understanding of common human experience. The richness of learning that results from the discussions held after a practice in taught sessions are therefore key in deepening understanding. If you are looking at an online course option, make sure the sessions themselves happen ‘live’, e.g. through platforms such as Zoom or Skype, with a trained teacher as per above.

Conclusions

We hope that the above has been useful in helping to wade through the baffling range of mindfulness training options. As a UK charity, we are keen to help support anyone on their mindfulness journey, particularly if their intention is to work with young people and/or those who care for them.

If you therefore want any advice or support in choosing a mindfulness training pathway, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.

By the way, since starting to write this article, the Google count of mindfulness training options has increased to 483,000,000. Just saying!

Further Information:

- Read more about current moves to regulate and quality assess mindfulness training here.

- Find out more about the .begin 8-week mindfulness programme here.

- Find a MiSP-trained teacher of the .b Foundations 8-week programme here.

- Find out more about the prerequisites for training to teach the .b or Paws b curriculum via the MiSP website.